Infantile Spasms West Syndrome

What are infantile spasms and what do they look like?

Infantile spasms (also called IS) are also known as West syndrome because it was first described by Dr. William James West in the 1840s. These seizures may be subtle and be confused with other normal baby behaviors or colic. IS can appear in different ways. Sometimes they may called “‘flexor spasms” or “jackknife seizures” due to their appearance.

- The spasms consist of a sudden stiffening. Often the arms fling out as the knees pull up and the body bends forward.

- Less often, the head can be thrown back as the body and legs stiffen in a straight-out position.

- Movements can also be more subtle and limited to the neck or other body parts.

- Infants may cry during or after the seizure.

- Each seizure lasts only a second or two, but they usually occur close together in a series. Sometimes the spasms are mistaken for colic, but the cramps of colic do not occur in a series.

- They happen most often just after waking up. They rarely occur during sleep.

Babies with infantile spasms often seem to stop developing as expected. Or they may lose skills like sitting, rolling over, or babbling. Often babies lose interest in their surroundings. They may interact less socially too.

Video Showing Examples of Infantile Spasms

Learn More:

Find Your Local Epilepsy FoundationWho gets it?

Infantile spasms are considered an age-specific epilepsy. They typically begin in an infant between 3 and 8 months of age. In most children, IS starts by 1 year of age and usually stop by 2 to 4 years of age.

IS is not common. Only one baby out of a few thousand are affected.

What causes infantile spasms?

Two out of 3 babies with IS have some known cause for the seizures, however the range of causes is broad.

- The most common cause is a structural change in the brain. This may be due to a prior injury (such as brain infection or lack of oxygen to the brain). It can also be due to a change in the way the brain has developed (cortical malformation or dysplasia).

- Genetic causes are also possible. There are a number of genes associated with spasms.

- Metabolic causes can also lead to changes in brain function and can cause spasms.

- Other babies have had no apparent injury and have been developing normally.

- There is no evidence that family history, the baby's sex, or factors such as immunizations are related to infantile spasms.

How are infantile spasms diagnosed?

- A careful history of spells, including what they look like and how often they occur.

- Make a video of the events and show them to your doctor if you are concerned your child may be having spasms.

- Find worksheets and forms to help you describe events in our Toolbox.

- A history of the child’s development and any prior brain injury.

- A physical and neurological exam.

- An EEG (electroencephalogram) looks at the electrical activity of the brain.

- An EEG in a baby with infantile spasms usually shows a pattern called hypsarrhythmia (HIP-sa-RITH-me-ah) when the seizures are not occurring. This high-voltage spike and wave pattern is often helpful in confirming the diagnosis.

- Most infants diagnosed with infantile spasms will need other tests like an MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) scan of the brain, blood and urine tests.

How are infantile spasms treated?

Medications

It is essential for infantile spasms to be treated as quickly as possible with the most effective therapies. Treatments that should be tried first before other therapies for children with infantile spasms include

- Steroid therapy with either prednisone/prednisolone or adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH)

- ACTH is given by injection into a muscle and prednisone or prednisolone is given by mouth to swallow.

- Side effects of steroid or ACTH therapy include infection, high blood pressure, stomach irritation, irritability, weight gain and puffiness.

- Vigabatrin (Sabril)

- This medicines comes as tablets or a powder that can be mixed into a solution and swallowed. It is given twice a day.

- Vigabatrin is a particularly effective option for children whose spasms are due to tuberous sclerosis complex.

- Vigabatrin has rarely been associated with permanent loss of peripheral vision, but this side effect is of more concern when the drug is used for many months. Long term treatment with vigabtrin is usually not needed for children with spasms. Monitoring vision in a baby on this drug is important.

- Studies are being done to see if combining steroids/ACTH and vigabatrin may be more effective for seizure control and improve a child’s development long-term.

- If the first two medicines tried (for example steriods, vigabatrin) don't work, other anti-seizure medications that may be helpful include: valproate (Depakote), topiramate (Topamax), pyridoxine (vitamin B6), zonisamide (Zonegran), clobazam (Onfi) or clonazepam (Klonopin). However, these medicines are less effective than steroids/ACTH and vigabatrin, so should not be used first.

If infantile spasms continue despite treatment with ACTH or steroid and vigabatrin, children should be seen by a pediatric epilepsy specialist to consider the best course of therapy.

Non-medicine Therapies

Epilepsy surgery should be considered early in a select group of children who have a focal area (specific location in the brian) leading to the spasms. This includes some children with tuberous sclerosis complex or malformations of the brain.

- In these children, there are often focal features to the spasms, such as head or eye turning to one side.

- EEGs are less likely to have a typical hypsarrhythmia pattern and may show more focal discharges.

The ketogenic diet has been reported to be safe, well tolerated and possibly effective for treating children with infantile spasms who do not respond to ACTH or steroid and vigabatrin.

What's the outlook for children with infantile spasms?

- Most children with infantile spasms have intellectual disabilities later in life.

- Children with IS have a higher chance of moderate to severe developmental delay if they have an underlying brain disorder or injury.

- The outlook is brighter for those who were developing normally before the spasms started – 10 to 20% will have normal mental function and some others may be only mildly impaired.

- Some children with infantile spasms develop autism.

- Treating seizures early and appropriately is critical to maximizing the child’s developmental potential.

- Even if the infantile spasms stop, most children later develop other kinds of epilepsy, including Lennox-Gastaut syndrome and focal or multifocal epilepsy. These types of epilepsy do not respond to medicines well.

Learn More:

Contact Our HelplineDr. West's Story

The first description of infantile spasms was by English physician Dr. W. J. West, more than 170 years ago. His description is as accurate today as it was then and is very poignant since he was describing his son.

“The child is now near a year old; was a remarkably fine, healthy child when born, and continued to thrive till he was four months old. It was at this time that I first observed slight bobbing of the head forward, which I then regarded as a trick, but were, in fact, the first indications of disease; for these bobbings increased in frequency, and at length became so frequent and powerful, as to cause a complete heaving of the head forward toward his knees, and then immediately relaxing into the upright position, these bowings and relaxings would be repeated alternately at intervals of a few seconds, and repeated from ten to twenty or more times at each attack, which attack would not continue more than two or three minutes; he sometimes has two, three, or more attacks in the day; they come on whether sitting or lying; just before they come on he is all alive and in motion, making a strange noise, and then all of a sudden down goes his head and upwards his knees; he then appears frightened and screams out; at one time, he lost flesh, looked pale and exhausted, but latterly he has regained his good looks, and, independent of this affection, is a fine grown child.”

Resources

Infantile Spasms Action Network (ISAN), convened by the Child Neurology Foundation (CNF), is a collaborative network of 26 national and international entities focused on raising awareness for infantile spasms. Find videos and more information at infantilespasms.org.

Tuberous Sclerosis Alliance, including more videos about infantile spasms

Infantile spasms information from the National Institute of Neuroloical Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) at the National Institutes of Health

Facebook Live on "Infantile Spasms and Access to Care" with Co-Editor-in-Chief of epilepsy.com, Elaine Wirrell MD.

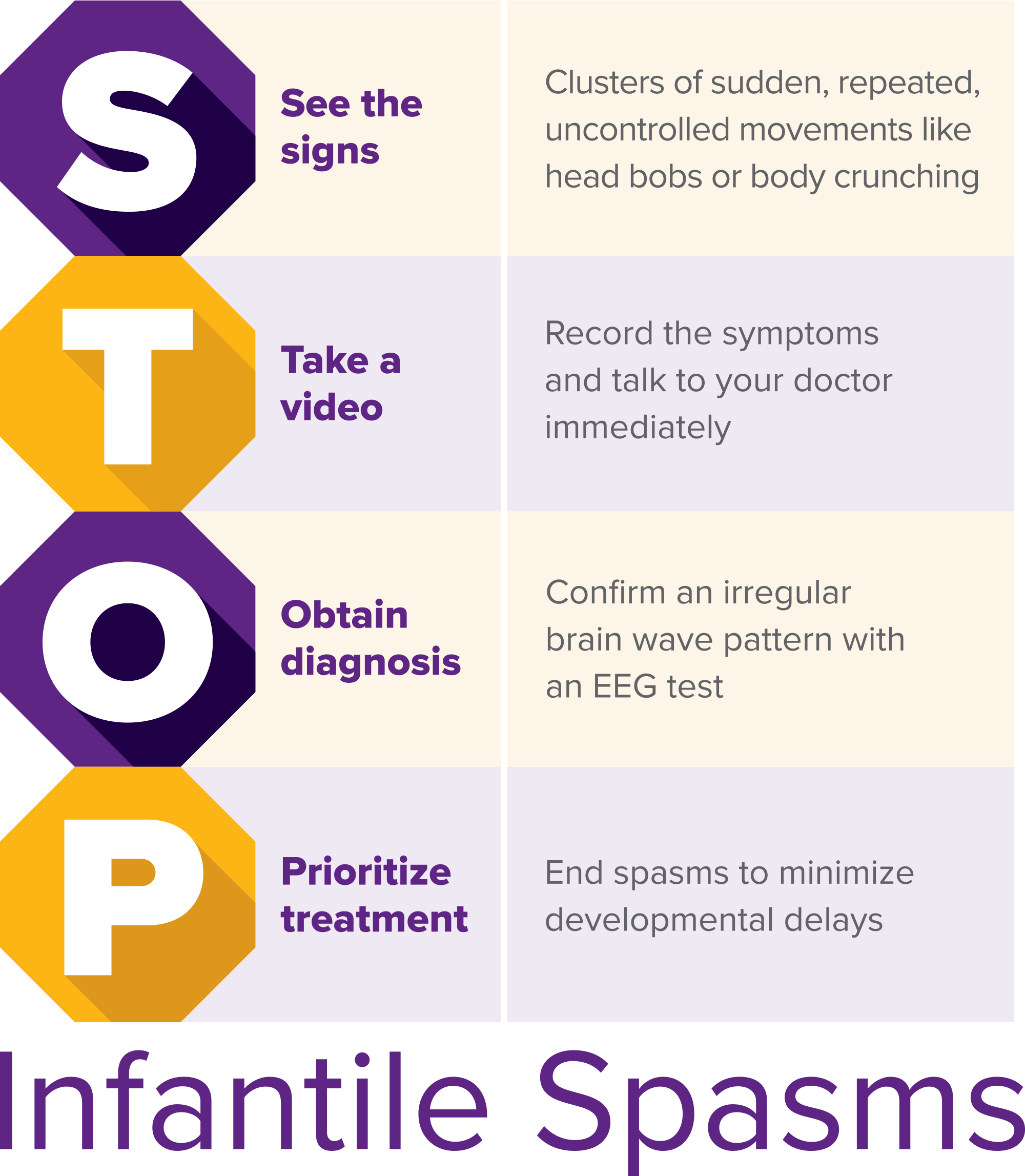

STOP Infantile Spasms

Although awareness efforts are year-round, Infantile Spasms Awareness Week (ISAW) is held annually on December 1-7. During ISAW 2017, the ISAN introduced the "STOP Infantile Spasms" mnemonic, an easily remembered acronym, to raise awareness about this rare, yet serious seizure disorder.

Resources

Epilepsy Centers

Epilepsy centers provide you with a team of specialists to help you diagnose your epilepsy and explore treatment options.

Epilepsy Medication

Find in-depth information on anti-seizure medications so you know what to ask your doctor.

Epilepsy and Seizures 24/7 Helpline

Call our Epilepsy and Seizures 24/7 Helpline and talk with an epilepsy information specialist or submit a question online.

Tools & Resources

Get information, tips, and more to help you manage your epilepsy.